News

Simon Lévy Retrospective

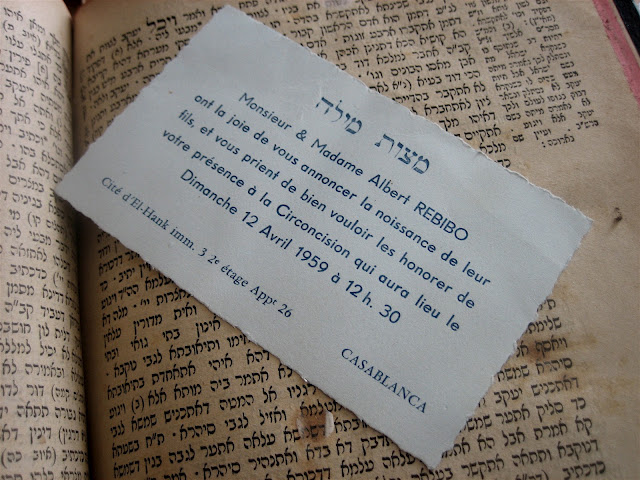

The following is a special to Diarna via Alma Rachel Heckman, a Wellesley alumna and UCLA graduate student in Middle Eastern and Jewish Studies. While a Fulbright scholar and Diarna researcher in Morocco, Ms. Heckman had the opportunity to work with and, after some concerted effort, to interview Simon Lévy, late director of Casablanca’s Jewish Museum. We present her account of that experience accompanied by a photo slideshow depicting many of the places referenced. Ms. Heckman previously wrote for Diarna about the razing of Casablanca’s Benchimol Hospital as well as Soulika, Morocco’s “Joan of Arc.”

Simon Lévy: Activist, Conservator, and Conscious Pariah

by Alma Rachel Heckman

Simon Lévy’s passing on December 2, 2011 marks the end of a singularly controversial and puissant Moroccan patriot, activist and conservator of Moroccan Jewish history.

Lévy was born in Fez, 1934. Since 1953 he worked for Moroccan independence from France, joining the Moroccan Communist party in 1954. He held several posts within the Communist party (later renamed the Parti du Progrès et du Socialisme or “the Party for Progress and Socialism”). Following his imprisonment during the “Years of Lead,” referring to king Hassan II’s suppression of dissent in the mid-1960s, Lévy continued his activism and work with the PPS, and began a prolific academic career as a linguist at Mohammed V University in Rabat. Between 1976 and 1983 he served as an advisor to the Municipal Council of Casablanca. In that capacity he worked to create local libraries and professional training centers. He edited and contributed to several Moroccan publications, including La Nation, Al Jamahir and Al Bayane. Since 1998 he served as the director of the Foundation for Moroccan Jewish Patrimony as well as Casablanca’s historical and ethnographic Museum of Moroccan Judaism.

For six months I worked in the archives of the Moroccan Jewish Museum in the neighborhood of l’Oasis in Casablanca, punctuated by interactions with Simon Lévy that revealed another side of the erstwhile conscious pariah. For months I asked to interview him, usually to be waved aside with the phrase “I’m in a bad mood, it won’t go well today!” or jokes about fat Americans and my vegetarianism. At his Mimouna party (a uniquely Maghrebi celebration at the end of Passover), he introduced me to mahia (a fig based liqueur traditionally made by Jews) while Mme Lévy explained the practice of wishing on fava bean pods and planting them in a bowl of flour. Though prone to shouting and the occasional vitriolic statement, Simon Lévy worked tirelessly with the Moroccan government, UNESCO, the Moroccan Jewish community and individual financiers to restore Jewish sites across the country, most recently Slat al-Fassayine, a synagogue in Fez.

Moroccan media heavily reported Simon Lévy’s death and funeral, with many prominent government officials in attendance. He was buried in the Ben M’Sik Jewish cemetery of Casablanca on Sunday, December 4. Below you will find excerpts from the notes I took from my interview with Simon Lévy in May 2010, in his office at the museum, regarding his own life and his thoughts on Moroccan Jewish history. The following may be read not so much for historical precision, but rather for a flavor of this prominent figure’s narrative of his own life and the history of Morocco. Unless otherwise indicated, all text is quoted from Simon Lévy.

On His Early Life:

Simon Levy was born on January 5th, 1934, in the French-constructed Ville Nouvelle (“New Town”) in a house that was “the third house built”there in 1918, outside the older components of Fez, which included the Mellah (Jewish quarter), Fes-Jdid and Fes al-Bali. He attended a French primary school between the ages of 3 and 7, and would spend his Thursdays and Sundays in the Talmud-Torah academy, called a msid, where the students memorized prayers and other sacred texts by rote. If the students failed to get something right, they suffered an “ancient method of punishment” called tahmila, which entailed beating the soles of the students’ naked feet with a baton. Simon proudly mentioned that in his youth he had organized the first student revolt against the practice of tahmila.

In Response to a Question about the Movement toward Moroccan Independence and Jewish Involvement therein:

The 1930s was the beginning of the independence movement, and simultaneously the coming of age for the Jewish youth that had grown-up after the establishment of the French protectorate. They had more contact with Europe than the previous generations because of their French education, and had direct contact with European anti-Semitism via French fascists in Morocco. Thus, they heard for the first time “sale juif”, or “dirty Jew”, in the streets of Morocco.

The Jews who supported Moroccan independence also demanded a classical Arabic education. In the traditional Jews schools, students learned about religion, the Gemara, to read the Torah, cantillation and how to write spoken Moroccan Arabic (darija) using the Hebrew alphabet – Moroccan Judeo-Arabic – but not classical Arabic. Simon sighed that now, no one reads Judeo-Arabic, and that it is a lost body of literature and a lost culture.

And what about the Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU)? Simon shouted and beat the table at this juncture: “The AIU only taught French” [not strictly true, AIU schools were predominantly in French with Hebrew lessons and often lessons in local languages]. According to Simon, the AIU was a French charity project that created “little French Jews” in foreign countries by its heavily Gallic education system. Students in the AIU schools “only had one tiny hour of Hebrew per week.” Simon went on to say that the AIU paved the way for French colonization in Morocco and the entrenching of an educational and political system based on “the superiority of Europe.” In this way, the AIU “destroyed Moroccan Judaism.”

In the 1930s, those Moroccan Jews that invested in the nascent independence movement wanted to be “truly Moroccan” alongside their Muslim compatriots, but there were other forces “working over” Moroccan Jews: the AIU, France and its cultural values, and Zionism.

On Morocco under Vichy Rule:

The Nazi regime never occupied Morocco, but rather controlled the Vichy French who did. In autumn 1940, Mohammed V signed the “Statute of Jews” into law. The Jews were astonished that the king could sign such a document, and protested.

The “Statute of Jews” stated that Morocco’s Jewish residents were no longer either subjects of king Mohammed V or of France, but that they were now “a separate category.” Jews were forbidden from practicing professions that they had traditionally occupied, including commerce, were barred from many educational opportunities and from other activities that were still allowed to Muslims and French people. Further, the numerous Jews that had moved out of the mellahs long ago and were now living in the Ville Nouvelles were required to move back into the mellahs, resulting in massive over-crowding, sanitation problems, and scarcity of resources. With this law, Jews were now Morocco’s “pariahs” rather than the king’s ahl al-dhimma or protected people.

Simon illustrated this with a personal story, relating that his uncle had built a nice, big house in the Ville Nouvelle of Fez in 1937. With the arrival of the war, he and his family were crammed into a single room in the mellah. This “hyper population” of the mellahs happened in every Moroccan city. Simon mused, “When I was young [during the war years], I remember standing on a balcony in the mellah of Fez. The streets were so over-crowded that the people were obligated to walk very, very slowly, in baby steps.” (Simon got up from his desk and demonstrated a slow, belaboured shuffle.)

On the Vichy Camps:

Simon encountered regiments of forced workers who were sent to the region of Fez to build roads and other infrastructure projects. For all of the cruelty inflicted upon them, they were allowed to attend Synagogue services, where they interacted with the Fassi Moroccan-Jewish population. Simon looked at his hands and said, “I remember throughout the war a certain Mr. Stern, who had led an easy life in France and was sent to work on the roads in Morocco.”

Simon’s father invited many of these forced-labor French Jews to the family’s home for Jewish holidays, where Simon observed the Ashkenazi way of celebrating Chanukah.

In November 1942, the Allies landed in Morocco for Operation Torch of the North Africa campaign. The arrival of the Allies “was the deliverance of Moroccan Jews from the German threat,” sighed Simon, who mentioned that Morocco had been lucky as compared to Tunisia, where the Germans had had a foothold and a prolonged presence. Simon added, “This period of French and European racism fundamentally changed the outlook of Jewish Moroccans. Jews had lost their jobs and their possessions, as well as their rights. After the war, it was different. This explains the wave of emigration from Morocco in 1948.”

On post-1948 Waves of Jewish Migration from Morocco:

In 1956, the year Morocco won its independence, life for Jewish Moroccans seemed quite good. There was Dr. Benzaquen, a Jewish minister in government, for example. However, more and more Jews were leaving Morocco for French educational opportunities, and were not coming back. During the war in Israel in 1956, Jewish community leaders adopted an anti-war stance “against the invaders.”

In 1964, the justice system of Morocco was “Arabized,” meaning that from then on, lawyers would have to work in Arabic. For the Jews who had graduated through a thoroughly Francophone educational system, this meant they were out of work. As a result, almost all Jewish lawyers left Morocco for elsewhere, including Simon’s own brother.

In 1967, Morocco’s Jewish community took no official position on the Six-Day War. When the Arab coalition suffered what was perceived as a humiliating loss on the military, political and international levels, Moroccan Muslims announced a boycott against Moroccan Jewish businesses in a “simplistic mind set” that equated all Jews with Israel’s military and political powers. The boycott lasted between 2-3 months, but the long-term effects were irreversible: the social and political climate in Morocco made Jews no longer feel safe. Many Jews left Morocco as a result, including Simon’s nephew, a doctor whose patients boycotted his practice. Even after this “ignorant boycott”, Simon estimates that about 30,000 or 40,000 Jews remained in Morocco.

The post-1967 steady drain of Moroccan Jews to France, Canada, Israel or the United States, was also on account of desires to attain a French education and upward mobility, as well as to reunite with family members who had already left.

On Moroccan Muslim Awareness of Jewish History:

“In 2004 and 2005, [the museum] commemorated the Casablanca bombings of May 16, 2003. We visited schools in order to explain that Morocco is not a country in which we kill each other. In one school, it was clear that all of the students but a small selected group had been excused for the day. These students had been groomed by their teachers with the proper answers to a variety of questions. As soon as I asked them to respond on their own, to deviate from the script, they said things along the lines that they approved of the terrorists, that they were now in heaven having worked for God. We brought them to the museum, and hopefully we opened their minds a little.”

At this point, Simon said he was expecting a visitor at 3pm. I walked with him out of the office, down the stairs and into the museum. He whistled merrily, sauntering ever so slightly. In the Moroccan fashion he kissed me once on each cheek and then a third time for good luck on the first cheek, wished me all the best luck and happiness in life, and then sauntered away, still whistling.