News

Now Screening: “Insights: Inside Queen Esther’s Tomb”

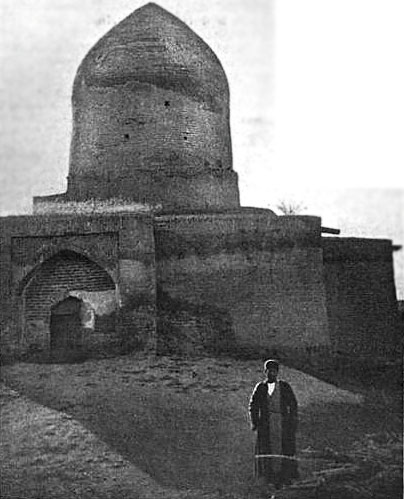

Hamadan, Iran –of all places– hosts one of the largest Jewish stars in the world. Just off Imam Khomieni Square in the center of the city is a pilgrimage site venerated by many Iranians as the burial shrine of biblical luminaries Esther and Mordechai. These heroes of the holiday of Purim —who according to tradition saved the Jews of the Persian Empire from genocide— are memorialized in a remarkable site that was specially renovated in the 1970s. Watch an interview with the site’s architect, walk inside a 3-D model, and see post-renovation photos smuggled out of Iran and only recently developed, and newly-discovered 100-year-old photos of the site.

This is the inaugural video of Insights: a Diarna series spotlighting Jewish sites across the Middle East. Insights is being made possible by a generous grant from the Elizabeth and Oliver Stanton Foundation. This month, against the backdrop of rising geo-political tensions, the series presents a Judeo-Persian shrine in northwest Iran.

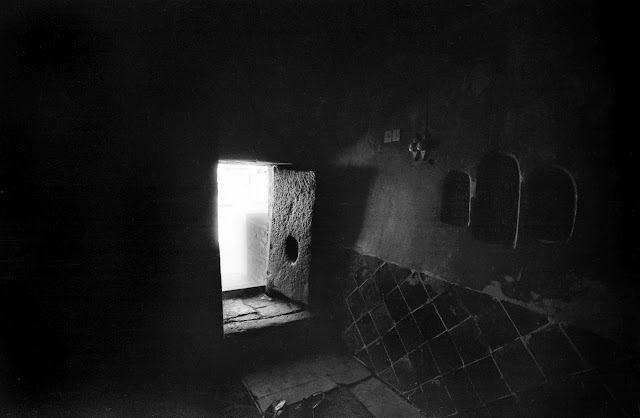

Entrance featuring granite door, exclusive post-renovation 1970s photograph (Courtesy of Yassi (Elias) Gabbay)

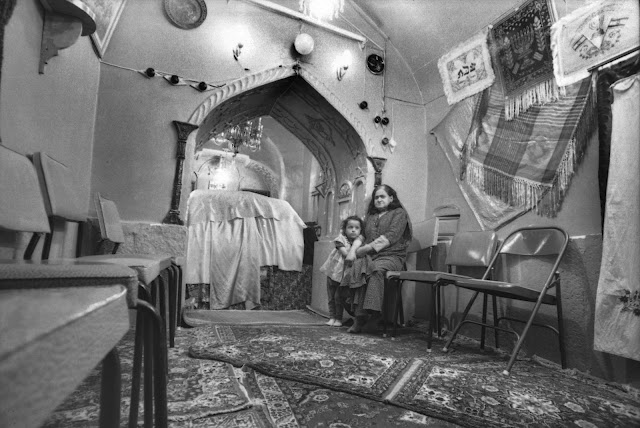

Just off Imam Khomieni square in Hamadan is a pilgrimage site venerated by many Iranians as the burial shrine of biblical luminaries Esther and Mordechai, the heroes of the Jewish holiday of Purim for saving Jews throughout the Persian Empire from genocide. Little known outside of Iran, secrecy, indeed a double secret, shrouds the shrine. According to the biblical book named after her, Esther was a peerlessly inspiring young Jewish woman who caught the eye of the Persian King Ahasuerus, became queen, and, with the assistance of her relative Mordecai, saved Jews throughout the Persian Empire from annihilation at the hands of the evil royal advisor Haman. Jews around the world celebrate this miraculous salvation during Purim by reading the Megillat Esther, dressing in costumes, and eating delicacies. Iranian Jews similarly mark the holiday, but for centuries have also made a pilgrimage to this shrine, which features intricate wooden sarcophagi and special sections for lighting candles in veneration of its namesakes.

The original shrine’s date of construction is unknown. Its date of destruction, at the hands of Mongol invaders, purportedly occurred in the 14th century. The first detailed accounts and illustrations in the historical record stem from 19th century Christian tourists, who observed how Jewish pilgrims would place prayer notes near the tombs similar to the custom associated with Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall.

The shrine served as a stand-in place at which to pray and weep for Iranian Jews who could only reach Jerusalem with great difficulty. While Iranians —including non-Jews– have been making pilgrimages to the site for centuries, outside knowledge of the shrine is limited. And even those who do know about the site remain mostly unaware of the story behind its renovation in the early 1970s. Yassi Gabbay was one of Iran’s most promising young architects when he was chosen by the Iranian Jewish community to rehabilitate the then-dilapidated shrine as their contribution to the celebrations honoring 2,500 years of Persian monarchy. Gabbay’s renovation preserved the shrine’s Persian and Islamic architectural elements while making it accessible from the main street via a bridge spanning the new courtyard. He added an iconic fence (since removed) featuring a “Jewish” or “six-point star, combined of two triangles” motif inspired by an Isfahani mosque ceramic.

Alongside the shrine itself, Gabbay built a subterranean synagogue with a roof ornament in the shape of a Magen David, quite possibly making Iran home to the only Jewish Star visible from space. The question of whether the shrine actually marks the resting place of Esther and her uncle remains unanswered, and is perhaps unanswerable. During the 19th Century, an American Christian pilgrim offered her own insight on the effectual significance of the shrine as well as the 2,700-year-old Persian Jewish community that guards it:

Beside the tomb of Esther the lowly race she saved have kept loving watch through all the weary ages. More wonderful than any ancient monument are these Jews themselves, lineal descendants, in blood and faith, of the tribes of Israel, and the only vestige of the truly olden time which entirely defies decay and dissolution.

Esther’s children in shrine antechamber, exclusive post-renovation 1970s photograph (Courtesy of Yassi (Elias) Gabbay)

Explore further by reading our full report “Esther’s Tomb: Iran’s Jewish queen defies decay and dissolution.” You can also watch the full interview with renovation architect Yassi Gabbay, who speaks in both English and Persian. And educators can download Discovering Purim: A Supplemental Curriculum from Diarna, an educational module that enables students to explore the holiday through the prism of geography.